Build Your Own Workbench Youtube 2019,Diy Wood Router Projects 60,Woodworking Furniture Design Books Free,Best Woodworking Shop Bench Edition - Step 1

It's less critical that the shelf be well supported along its length. Do a trial layout to see how the parts fit together. Label each part to indicate which part joins with which. Mark the holes The holes we want to mark are the holes through which the threaded rod connecting the two legs will run. The hole for the upper stretcher has to be positioned so that when the rod is running through this groove, the top of the short stretcher is even with the top of the legs.

The most precise way I've found for marking the position of this hole is to use a dowel center. Fit the dowel center into the bottom groove, line up the stretcher, and bang on the end with a rubber mallet.

The dowel center will leave a mark indicating the center of the hole. The precise position of the lower stretcher is less critical. I marked out a position 8" from the end of the legs. Drill the holes In the "Getting Started with Woodworking" video, the holes through the 4x4's were drilled from the back. That is, they start on the side opposite the precisely-positioned mark, and drill through to hit it.

I drilled from the mark. That way I could ensure that the hole was where it was supposed to be, on the side where the position was critical. Brad-point bits are far more precise than twist bits -- they're more likely to start where you want them to, and they're more likely to stay straight. So I started each hole with the brad-point bit, then finished it off with the twist bit.

I clamped a piece of ply on the back, to reduce tear-out. When the holes were complete, I flipped the legs and drilled the countersinks with a 1" Forstner bit. Trying to drill a countersink when the center was already drilled would be impossible with a spade bit or an auger, but Forstner bits are guided by their edges, not their center, so they can handle this job. On thing about Forstners, though -- they have a tendency to skitter around a bit when starting, before they bite.

An easy fix for this is to drill a hole through a piece of ply, and to clamp that to your work, creating a jig that will prevent the bit from drilling in the wrong spot. The countersinks should be deep enough to hold a nut and washer, plus a little bit. These stretchers already have a groove running their length, centered on the bottom edge. Precise placement isn't necessary, but keeping track of which part is which is.

We need a hole in each end of each stretcher. Take care to keep these holes square, you don't want them running at angles. Mark the leg dowel holes Lay a leg flat on your work surface, with the countersink side of the thru-holes down.

Stick a piece of threaded rod in each hole. Take a stretcher that is marked to have one end adjoin the top of this leg, stick a dowel center in its dowel hole, line it up against the leg, using the threaded rod for positioning, You want the top of the stretcher to be even with the top of the leg, or just slightly above it. Give the end of the stretcher a whack with your rubber mallet.

This will leave a mark indicating where the matching dowel hole in the leg needs to be drilled. Repeat with the lower stretcher than adjoins this leg. Then repeat for the other leg that will form this trestle, and the other ends of the two stretchers. Drill the leg dowel holes When you have both legs for this stretcher marked, drill the other dowel holes at the marks. Again, take care to make the holes square.

A board jack is mechanism to provide support to long boards that are being held in the vise. These can be quite sophisticated, involving parts that can be moved both horizontally and vertically.

The simplest mechanism is simply to stick a dowel into a hole drilled into the front of your bench. The "Getting Started in Woodworking" video showed only one hole, drilled in the right front leg, level with the vise.

This is useful only for a narrow range of boards. I decided to drill holes at four different heights in each of the front legs, six inches apart. The Jig Drilling a precisely positioned, deep, wide hole isn't easy, without a drill press. So I bought a WolfCraft drill guide. After experimenting with it, and drilling some test holes, I build a jig around it. To mark the centerline, set a compass to span something more than half the width of the leg. Draw an arc from corner of the leg.

The point where the arcs intersect will be on the centerline. With a centerline point on each end of the leg, place a scribe on the point, slide a straightedge up to touch the scribe.

Do the same on the other end. When you have the straightedge positioned so that you can touch both points with the scribe, and in each case it is touching the straightedge - without moving the straightedge - scribe the line. Use scribes, rather than pencils or pens, because they make more precise marks. Then mark the second hole on the centerline, six inches below the first. Repeat for the other two holes. To precisely set the span of the compass, use a rule with etched markings, and set the points of the compass into the etched grooves.

Place a centerpunch on each of your four points in turn, and press down to make an indentation. This will mark the center of the hole. Drilling the holes Because of the depth of the holes, drilling each hole became a four step process: 1. Flip the leg, position the jig, and finish the hole off with the Forstner bit. This gives a clean exit. The top hole on each does not extend through, and only steps 1 and 2 are necessary. If you bought 6' lengths, cut off two 24" long lengths. On one end of each, place a washer and a nut.

Screw on the nut only half way, you don't want the end of the rod protruding. Thread the rods through one of the legs, then set the leg flat on the table. Insert dowels into the dowel holes. Place the matching stretchers into place. Put dowels into the dowel holes at the top end of the stretchers. Place the other leg onto the threaded rod and settle it down onto the dowels.

You'll probably have another opportunity to whack away with your rubber mallet. When you have the other leg seated, the threaded rods will extend father than you want them to. You'll want to mark them so they can be cut to length. Place a washer and a nut on each threaded rod, and then tighten down the nut to pull everything tight. Depending upon the wrench you are using, and how much longer the rod is than it needs to be, you may find it necessary to stack up a number of washers, so that the nut is positioned where the wrench can operate on it.

Once you have pulled everything tight. You want to cut it slightly below flush. Then take everything apart. Cutting the rods There's nothing very tricky about cutting the rods.

Clamp them to your temporary table, and cut them off with a hacksaw. Make sure you're using a sharp blade. While you're setting up the clamps,.

The hacksaw will often damage the last thread when it cuts. Running a nut off the end will fix this. You'll have to run the nut all the way down from the other end. This doesn't take long, if you chuck up the rod in your drill and let it do the work. Hold the rod vertically, with the drill pointing down, and just hold on to the nut enough to keep it from spinning. Assembly When you have the rods cut to length, put everything together the way you did before, and you'll have your first trestle.

Repeat the same process for the second trestle, and then for long stretchers to assemble the base Once the stretchers and legs have been connected, flip the assembly upside down, and install the levelers. Then flip it back upright. Next is the shelf. Start with the 24x48" piece of MDF. Clamp this on top of the base, and pencil in the outside of the stretchers and the inside angle of the legs. Flip it over, pull out your trusty cutting guide, and cut it to width and to length. Cutting out the angles is simple, with a jig saw.

It's not much work with a hand saw. If you took enough care with supporting blocks and stops, you could probably do it with a circular saw. Since I did have a jig saw, I used it.

I'd decided on an oil-and-wax finish. Oil finishes are by no means the toughest. In fact, they're really rather pathetic, so far as protecting the wood goes.

But they're easy to apply, and not even the toughest finish will stand up to the abuse that a workbench will suffer, so it's more important that it be easy to repair. Wax is usually used to add a high gloss. On a bench, it's there to keep glue from sticking. And then decided that the oil alone would be sufficient for the base. The wax serves to give the surface a gloss which I see no need for , and to make it easier to remove spilled glue and paint which I also see no need for, on the base.

So I oiled the base and oiled and waxed the top. The "Getting Started in Woodworking" video series has an episode on applying oil-and-wax finishes, that includes steps such as wetting the wood, and then sanding down the raised grain. All of this seemed excessive, for something that I was going to put in my basement and bang on with a hammer. I made a low table out of a couple of step-stools, my hollow-core door, and one of the MDF panels that would eventually form part of my top.

I was concerned that any oil that dripped on the door might interfere with its glue adhesion, when I finally get around to the project for which I'd purchased it.

The top side of the top sheet of MDF, though, I planned to oil, anyway. Ditto for the bottom side of the bottom sheet. Putting the base up on this temporary table put it an a more convenient height than it would have been on the floor or on a full-height table. Applying the oil is easy. Put on some vinyl gloves, pour some oil in a bowl, take a piece of clean cotton cloth the size of washcloth or smaller, dip it in the oil, and apply it to the wood.

You want the wood to be wet. Apply oil to the entire surface, and then go over it looking for dry spots, applying more oil as needed.

After fifteen minutes of keeping it wet, let it sit for another fifteen minutes. Then apply another coat of oil, and let it sit for another fifteen minutes.

Rub it dry. Wait half-an-hour, and then wipe dry any oil has seeped out. Check it every half hour and do the same, for a couple of hours. The next day, apply another coat, wait half an hour, then wipe it dry. Do the same on successive days for as many coats as you think are necessary. I applied three. Remember those fire safety tips you used to get in grade school, about the dangers of oily rags? It was linseed oil they were talking about. All oily rags are dangerously flammable.

Linseed oil will self-combust. Linseed oil doesn't evaporate, it oxidizes. The oxidization generates heat, and the increased temperature increases the rate of oxidation.

Linseed oil sitting in a bowl, or spread on the surface of wood, is perfectly safe. But a linseed oil soaked rag provides a vastly increase surface area, so the oxidation happens faster, and the rag can provide insulation, trapping the heat. The increased temperature speeds up the oxidation even more, which raises the temperature even more, and the runaway feedback can quickly result in temperatures that will cause the rag to spontaneously burst into flame.

This isn't one of those "do not drive car while sunscreen is in place" warnings. This is one of those "keep your finger off the trigger until you have the gun pointed at something you want to shoot" warnings. Rags soaked in linseed oil will catch fire, if you don't handle them properly, and they can do so far more quickly than you might think. Hang them up outside, away from anything combustible, and where there's enough air circulation to keep them cool. Or put them in a bucket of water, and hang them outside later.

If you're just setting a rag down for the moment, set it out flat, without folds, on something non-flammable. Hanging outside in the breeze, the oil in the rags won't retain heat while they oxidize. For the oil to completely oxidize can take in a couple of days, if it's warm, or more than a week, if it's cold and rainy. When fully oxidized, the oil will be solid and the rags will be stiff. At that point, they're safe, and can be thrown in the trash.

Toss them in the trash before that, and you might as well say goodbye to your garage. Before you start cutting or drilling the pieces that will make up the top, determine the layout of the top. This should include the dimensions of the MDF, the dimensions of the edging, the locations of the vises, and of the screws or bolts that will support the vises, and of all of the benchdog holes and of all of the drywall screws you will use to laminate the panels, If you don't lay it all out in advance, you could easily find that you have a bolt where you need to put a benchdog hole, or something of the sort.

I sketched out ideas on graph paper, then drew the plan full-size on the top side of the bottom layer of MDF, using the actual parts as templates. The width of the top is determined by the width of the base. The length of the top depends upon the vise or vises you uses. The end vise I had purchased was intended to be used with hardwood jaws that extend the width of the bench.

I had a piece of 2x6" white oak I intended to cut down for the purpose. The decision to be made with respect to the end vise is whether the support plate should be mounted to on the inside or on the outside of the stretcher. Mounting the plate on the inside of the stretcher reduces the reach of the vise - it can't open as far, because the support plate is back from the edge by a couple of inches.

But mounting the plate on the outside of the stretcher means that we need to add some support structure for the inner jaw of the vise, which the legs would have provided if we'd mounted the plate on the inside. I mocked up the two scenarios, and determined that with the plate inside the stretcher the vise would have a reach of 8 inches, and with it outside the stretcher it would have a reach of 9 inches.

I decided that 8 inches was enough, and that the extra inch wasn't worth the extra effort. With the end vise mounted like this, the right edge of the top would have no overhang. I wanted the left edge of the jaw of the front vise to be flush with the left edge of the top, the right edge with the left edge of the left front leg. So the amount of overhang on the left depends upon the width of the front vise jaw. The width of the jaw is, at a minimum, the width of the plate that supports it, but it's normal to make the jaw extend a bit beyond the plate.

How far? The more it extends, the deeper a bite you can take with the edge of the vise, when, for example, you are clamping the side of a board being held vertically. But the more it extends, the less support it has. What you need to determine, by this drawing, is where you need to drill the dog holes, the mounting holes for the vises, and where you will put the drywall screws you'll be using for the lamination.

As well as where the edges of the top will be cut. The next step is to laminate the two sheets of MDF that will make up the lower layers of the top.

First, trim the MDF to slightly oversize. You'll want room to clean up the edges after the pieces are joined, but you don't need more than a half-an-inch on each side for that, and there's no point in wasting glue. If you're lucky enough to have a vacuum press, use that.

Otherwise drill holes for the screws in the bottom layer at all the points you had indicated in your layout. You'll also want to either drill a row of screws around the outside edge, in the bit you're going to trim off, or you'll need clamps all around the edge. I just added more screws. The screw holes should have sufficient diameter that the screws pass through freely. You want the screw to dig into the second layer and to pull it tight against the first.

If the threads engage both layers, they will tend to keep them at a fixed distance. If you're using drywall screws, you'll want to countersink the holes.

Drywall screws are flat-head, and need a countersink to seat solidly. If you're using Kreg pocket screws, the way I did, you won't want to counter-sink the holes. Kreg screws are pan-head, and seat just fine against a flat surface.

Both drywall screws and Kreg pocket screws are self-threading, so you don't need pilot holes in the second sheet of MDF.

Regardless of which type of screw you use, you'll need to flip the panel and use a countersink drill to on all of the exit holes. Drilling MDF leaves bumps, the countersink bit will remove them, and will create a little bit of space for material drawn up by the screw from the second sheet of MDF.

You want to remove anything that might keep the two panels from mating up flat. I set a block plane to a very shallow bite and ran it over what was left of the bumps and over the edges. The edges of MDF can be bulged by by sawing or just by handling, and you want to knock that down. After you have all the holes clean, set things up for your glue-up. You want everything on-hand before you start - drill, driver bit, glue, roller or whatever you're going to spread the glue with, and four clamps for the corners.

You'll need a flat surface to do the glue-up on - I used my hollow core door on top my bench base - and another somewhat-flat surface to put the other panel on. My folding table was still holding my oak countertop, which makes a great flat surface, but I want to make sure I didn't drip glue on it so I covered it with some painters plastic that was left over from the last bedroom we painted.

Put the upper panel of MDF on your glue-up surface, bottom side up. Put the bottom panel of MDF on your other surface, bottom side down. The panel with the holes drilled in it is the bottom panel, and the side that has the your layout diagram on it is the bottom side. Chuck up in your drill the appropriate driver bit for the screws your using.

Make sure you have a freshly-charged battery, and crank the speed down and the torque way down. You don't want to over-tighten the screws, MDF strips easily. Once you start spreading glue, you have maybe five minutes to get the two panels mated, aligned, and clamped together. So make sure Build Your Own Mirror Frame Youtube you have everything on-hand, and you're not gong to be interrupted. Start squeezing out the glue on one MDF panel, and spreading it around in a thin, even coating, making sure you leave no bare areas.

Then do the same to the other MDF panel. Then pick up the bottom panel and flip it over onto the upper panel. Slide it around some to make sure the glue is spread evenly, then line up one corner and drive in a screw. Line up the opposite corner and drive in a screw there. Clamp all four corners to your flat surface, then start driving the rest of the screws, in a spiral pattern from the center.

When you're done, let it sit for 24 hours. The edges of MDF are fragile, easily crushed or torn. MDF is also notorious for absorbing water through these edges, causing the panels to swell. This edging is one of the complexities that Asa Christiana left out in his simplified design. I think this was a mistake.

MDF really needs some sort of protection, especially on the edges. Of course, I, on the other hand, with my Ikea oak countertop, probable went overboard in the other direction. I clamped the countertop to my bench base, and used the long cutting guide.

I'd asked around for advice on cutting this large a piece of oak, and was told to try a Freud Diablo tooth blade in my circular saw. I found one at my local home center, at a reasonable price, and it worked very well. Remember, you want the width of the top to match the width of the base, and you're adding edging.

First, cut one long edge. Second, cut a short edge, making sure it's square to the long edge you just cut. Finally, cut the remaining short edge square to both long edges. The length of the top doesn't need to precisely match anything, so we don't need to bother with clamping the trim before measuring.

Glue up the trim on the end, first. Do a dry fit, first, then as you take it apart lay everything where you can easily reach it as you put it back together again, after adding the glue.

To help keep the edge piece aligned, I clamped a pair of hardboard scraps at each end. I used the piece of doubled MDF I'd cut off the end as a cawl, to help spread the pressure of the clamps. Squeeze some glue into a small bowl, and use a disposable brush. As you clamp down, position the trim just a little bit proud of the top surface. Once you have all the clamps on, take off the scraps of hardboard.

You can clean up the glue squeezeout with a damp rag.. When the glue is dry, trim down the strip flush with the panel using a router and a flush-trim bit. Then cut off the ends of the strip with a flush-cut saw, and clean up with a block plane, an edge scraper, or a sanding block. Leaving the ends in place while you route the edge helps support the router. The strips along the front and back edge is glued up the same way. I suppose you could try to glue both on simultaneously.

Will be building it soon. Any ideas on how to incorporate a flip top on the other end for a miter saw? Or any other suggestions would be great! The only question I had was regarding on how you affixed the legs to the the frame in step 2. Did you join the legs together first before attaching them to the frame? If you joined the legs together prior to attaching them to the frame, what size screws did you use?

You could attach the legs together before attaching them to the frame, but I just found it easier to attach them straight to the frame first.

Just built this today, although a slightly bigger version. Thanks for the inspiration and guidance. I really appreciate it. What is the final height from floor to table top?

I may need to adjust the height some. I do not have a garage only a shed. Instead of the long permanent table off the back, do you think I could put one of the folding wings, like from your miter saw table or would that make it too heavy on the backside when opened? Another option is that you could build a separate mobile table and pull it around to the back when you need to use it.

I am getting ready to build this table, I got all the materials today. I was wondering if you had an recommendation of building my own or buying one on a tight budget that would work with this table? Thanks for using my plans! I just started woodworking in the last year and I am loving it. For Mothers day my husband gave me a jigsaw, router, another drill. And he ordered me a table saw. I had seen your plans for this table, so I got all the materials and started putting it together.

I finally got my table saw today and it fits in perfect. Thank you for your plans. Great build. Easy to follow directions. This leaves a large opening for the sawdust.

I used the original box that the tablesaw came. Cut it down to fit under the saw. I just pull out the box and dump the dust out. What an awesome build! Just a question for a complete beginner…. What is the blade diameter for your table saw? If you decide to go with a different size, you can always just adjust the little shelf to fit your saw. Not quite getting it. Hello, My name is George! I had a lot of fun making it and it really helps keep my workshop organized!

Thank You. Hi to All. Great idea. Apologies if this duplicates something already said. There are too many comments to read.

In my experience, wheels must withstand a LOT of force. Make the wheel attachment more robust. Get the hardest wheels you can to roll well on debris-covered concrete. Be sure table corners are exactly square. You can use the table edges to guide tape measures, squares, etc.

Hope ideas help someone. Very nice plans! I took them yesterday, got the lumber last night and assembled today! I added a miter saw shelf that is removable to have one large flat surface or I can put the miter saw in and have the long-side to work.

Sorry about the misspelling on the first one. If you want to be able to download the plans, you may purchase the PDF version. I have to use a different software to create downloadable plan sets and they take a lot longer to put together, so I charge for them.

If you prefer the free version, use the diagrams from this post. Hi there, you should have received an email right away with a link to download the plans. It may not be in your main inbox — make sure to check your spam folder. Please email me at [email protected] if you still have trouble finding them. Thank you so much! The measurements were spot on, I cut all the 2x4s and then assembled. You made it so easy. And it works great. Thanks so much for building from my plans — I hope you get tons of good use out of it!

I just finished the bench project. This was my very first wood shop project ever. It came out amazing! Thank you!

I have a Bosch — that I am thinking about putting the saw at the side of the table vice at the end — giving my fence a little more room to extend outwards to 41 inches from left to right — making the table a little deeper and adding a second table for my chop saw that I can butt up when I need extra space for run out from the table saw.

But I like you plan for a good simple table that I can make work. Great write-up! I am in the process of building this now. Got the table saw for Christmas. My first ever. Still in box but table is all but top complete. Excited to use this. Hey Jason, i agree on people and power tools. But it is never too late to learn. I am a 62 year old grandmother and am looking forward to what possibilities are out there for a new wood worker!!

But your picture shows the top flush with all of the 6 vertical legs. I edited the plans a little after I built my workbench so you can clamp anywhere. Hi Tylynn! I was planning to build this workbench but thanks to covid my shop aka bonus room has to double as a secondary work-from-home office. I was thinking I can still go ahead and build the workbench without the cutout for the table saw and maybe paint a bit.

Do you recommend any changes to the tabletop? Totally up to you and how much space you want to save! Just did this build, thanks for the solid plans. I tweaked it to be quite a bit shorter and cut bevels and channels to fit the DeWalt rack and pinion fence. I also used retractable casters since that seemed more stable vs. I may add a drawer or three, power strip and vice.

As I was fiddling with the shelf height to ensure the table saw surface would be perfectly flush with the work table, I wondered if as the lumber settles, I could lose flushness. This got me thinking that maybe the shelf for the table saw should be located on all-thread, or something that could easily raise and lower the shelf by a few millimeters.

Of course you can shim, but cooler designs are more fun to ponder. Perhaps losing flushness is a non-issue.

Probably depends on how you build it, but I think you should be fine. Your email address will not be published. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. I used glue and my brad nailer for this. I also used a spacer to make getting the height the same on all of them. I personally made my bottom shelf higher than the top, but I recommend getting an idea on what you want to store here before determining the height of these.

Next up was to cut the shelving bottoms to fit on top of these rails and in between the dividers. If you want, you can make them permanent and nail them to the rails. To prevent things from falling off as I pull the shelf out, I cut then attached two side walls for each cubby. Then on the front, I also cut and attached a piece that acts as not only a stop block to keep the shelf from just going back into the space, but also as a convenient hand pull for the shelf.

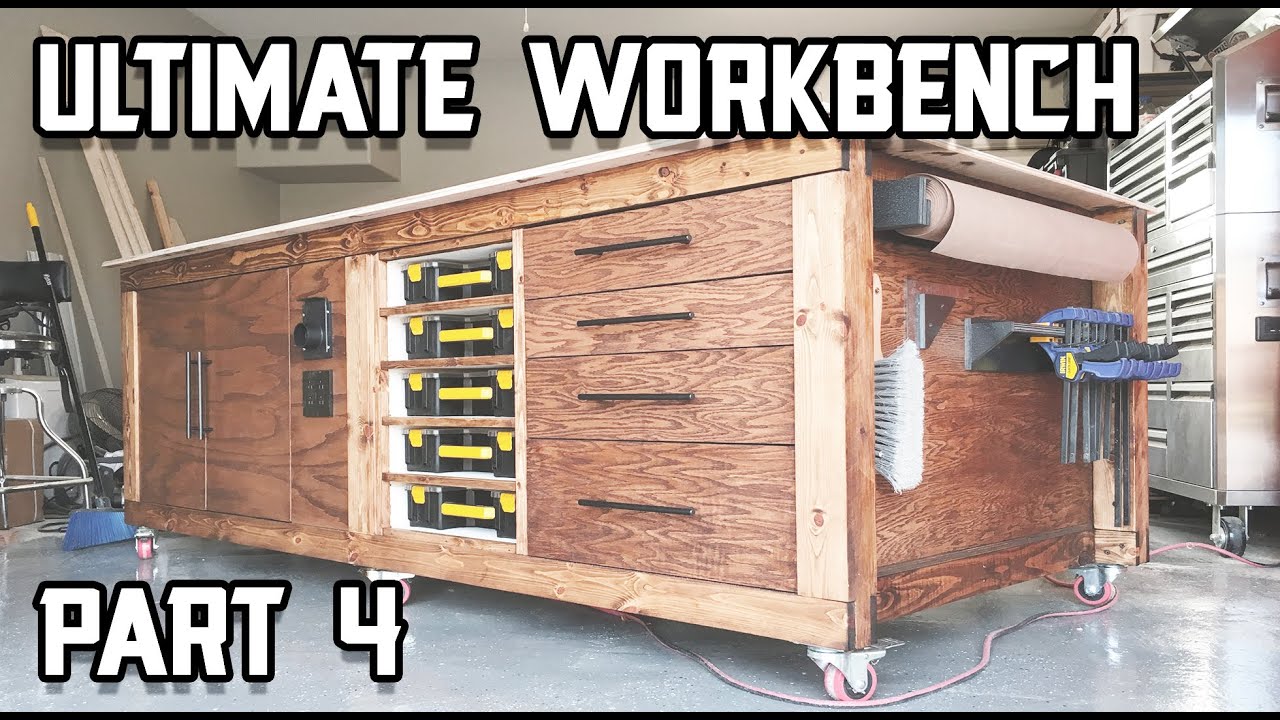

To prevent the shelf from just falling out, I cut some strips and attached them directly up front and above the side walls of each shelf. Now I can pull each shelf almost all the way out without it falling. Moving on to adding a bench vise. To add one on my workbench, I have to place it on one of the ends. I first jointed an edge and a face on some maple I had, then ran the pieces through the thickness planer to get the second face flat.

Now I could take the center section of the vise, transfer the hole location to my wooden piece, then use a forester bit and drill press to punch out the holes. I made sure to hit the two end grain surfaces first then the long grain after. This just gives you a better result. Then built up the side area on my workbench that I would be attaching the vise. Now could transfer the hole location to punch through the side of the bench, then attach that center vise section to the built up blocks.

Last thing was to stab the hardware through the attached center section, then unpackage and attach the handle which comes in three parts. And now I have a working bench vise. Next modification was to make a down draft table. You typically see these as stand alone builds but I thought it would be cool to incorporate one directly into the top of my workbench. You sand on top of it, since it has a holy top surface, then add vacuum to the underside to pull and collect the dust.

|

Japanese Carving Tools Online Wall Cabinets Knobs And Pulls Make |

spychool

11.08.2020 at 13:57:48

RASIM

11.08.2020 at 10:42:43

STUDENT_BDU

11.08.2020 at 14:44:44